This is an adaptation of a presentation delivered to conferences including Write the Docs Portland 2020, Ohio Linuxfest OpenLibreFree 2020, and FOSDEM 2021. The presentation source is available at GitHub and recordings are available on YouTube. This is a two-part post that will share both the requirements and execution of the documentation workflow we built that is now used by many of our teammates and leaders. Read part two here.

Introduction

Our manager came to my team one day and told us about an upcoming off-site meeting at which we'd be asked to present the work we'd been doing on a multi-year machine learning project. A part of that necessitated a write-up detailing how our product worked at a high level.

Multiple people would be consuming it: executives would receive a high-level summary, senior directors would receive a briefing primarily about logistics, and our director would expect a deep dive into the nitty-gritty details, but we didn’t need to put lots of code into the document.

We knew we needed to provide deep content coverage, but it needed to be well-summarized and be navigable. We knew that we needed a well-designed document that could be easily read when printed but also take advantage of the aspects of the hypermedia used to distribute it digitally. We'd most likely deliver a PDF, but a long web page wasn't off the table.

Then there was a big change: our product development was to be paused, so we needed to document everything. It may not be our team that continued development, if and whenever development may continue.

This meant that our audience grew to include ourselves and our successors: data scientists and engineers supporting a production system. This expanded scope would necessitate in-depth detail to capture the knowledge of our team for posterity's sake.

What we intended to be a quick and easy project turned into something much more detailed and in-depth than we could anticipate.

Designing a Document Process for a Team

We had seven people on the team and all of us had something unique to contribute. Many of the areas of the product enjoyed a lottery factor greater than zero, but some did not. Meaning, in areas with a zero-lottery factor, there are zero other people who know about that area if the one person who’s currently responsible for it wins the lottery and suddenly leaves the company!

We each had different concerns and interests to be recorded in the document. The engineers needed to show how the product works and how it's deployed as production software. They cared about architecture, implementation, and serviceability. The data scientists needed to show the business logic behind that software, including equations and citations, with a veritable cornucopia of acronyms, initialisms, and other terms likely requiring the need for a glossary.

We needed something we could all easily use and to which we could contribute simultaneously. After all, we had just a handful of days to complete this document. We needed a workflow that would get out of the way and let us focus on the content while still looking clean and professional.

Our need: a content-focused, scientific document authoring workflow for data scientists and engineers alike.

From FIRST Principles to Architectural Quality Attributes

Experience and great coworkers have taught me to think architecturally and to design from first principles. It is good practice to first figure out the things that you value about a system before you start building it. When I am building software, after the initial idea comes but before I start engineering a system from it, I think about quality attributes.

We assumed that our content would be lots of text, diagrams, and equations. We wanted a content-focused markup format that was easy to read and preferably didn't require a special program to read. We really liked text files. That is, we wanted it to be reviewable on GitHub. Also, we wanted not to be able to control styling within the document, except perhaps for calling out special sections using semantic markers; we wanted to minimize structural exceptions with standardized styling and typesetting.

Given the domain, we wanted to be able to use LaTeX, a popular typesetting system and programming language friendly to mathematical publishing, if we needed it. We knew that we might want to draw a diagram using TikZ, the one of the diagram packages for LaTeX. We also acknowledge that some of our team may prefer to write their section in LaTeX directly instead of a simpler format, such as Markdown.

Lastly, it needed to be easy to use for humans and computers: one command should build the document and we should treat that document as a build artifact that is versioned and archived.

Treat Documentation as Source Code

The key idea is this. This concept of treating documentation as source code is probably not novel to most seasoned documentarians, but for those to whom documentation is all-to-often an afterthought, this concept might be life changing.

We wanted to avoid these things at all costs through:

- Binary files or XML

- Passing around a file via email or Slack

- Manual copy-paste to merge changes

- Difficult exports from wiki format

- Forcing everyone to (re)learn LaTeX

This basically eliminated Microsoft Word, Apple Pages, straight-up LaTeX, our Confluence wiki, and virtually every lesser-known text format. We considered some of the newfangled tools like mdBook but found that they did not have the quality of PDF output and integration with the niceties of the Pandoc ecosystem.

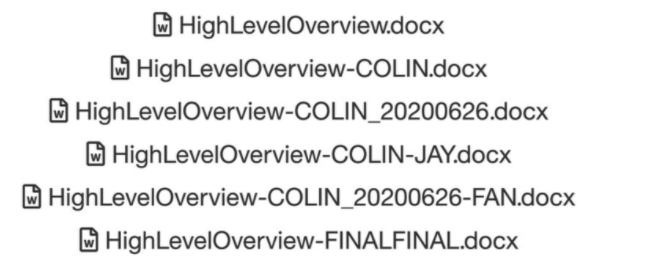

We really wanted to avoid this mess of poorly named files, confusingly manually merged with things forgotten or missed.

The (mostly) Open-Source Solution

Given these requirements, values, and our skills with automation, we built a solution based on Pandoc in combination with Git, GitHub Enterprise, and our Drone continuous integration system in about two weeks, while also writing prose.

This got us simple text, easily read, reviewed, agreed upon through our established systems of consensus, and produced the same way every time. We could easily distribute changes and settle conflicts. We could easily build the document locally but also release it just like software. What is a document if not software for the human mind?

It could even automatically notify stakeholders when we released a major new version. We really liked this because we could show people that we were making consistent progress by directly sending updates to their inboxes.

The biggest benefit in the end was exploiting LaTeX typesetting, something we all loved, without suffering through writing LaTeX. Well, at least only having to write LaTeX when we really needed it for a specific section. Our final document had very little raw LaTeX in it outside of equations and a couple of diagrams that were simple enough to be quickly redone in TikZ instead of leaving them as PNG or SVG images. Doing this created much higher quality images in the final product PDF.

Once we identified the solution, the next step was extending work in Pandoc and other tools to collaborate on, build out, and deliver our document. Read part two of this post, with details on how these requirements came together with our learnings to ultimately create the documentation workflow process that is now used by many of our teammates and leaders.

RELATED POSTS

Executing a Documentation Workflow

By Colin Dean, April 6, 2022

This post is the second in a two-part series about creating a documentation workflow for data scientists and engineers. Click here to read the first post. This is an adaptation of a presentation delivered to conferences including Write the Docs Portland 2020, Ohio Linuxfest OpenLibreFree 2020, and FOSDEM 2021. The presentation source is available at GitHub and recordings are available on YouTube.